by Dr. Danielle Bradley

Almost every teacher has heard the overwhelming and unanimous groans when announcing it’s time for students to write.

Writing assignments are not usually a crowd favorite, and often teachers struggle to make this instruction meaningful and even fun.

So how does the teacher avoid grading hundreds of unimpressive writing samples while also garnering buy-in from students? The answer is scaffolding writing lessons.

What is scaffolding?

Scaffolding in education is a technique that allows teachers to use various levels of support while helping students reach higher levels of comprehension and independence. In basic terms, scaffolding involves breaking up concepts or skills into smaller parts and then providing the assistance for students to learn each component.

Scaffolding lessons can be incorporated into any classroom K-12 or at the college level. This strategy works great with any curriculum and level of learner as well. Whether a new or veteran teacher, slowing down the pace of teaching challenging content is a win for the teacher and students.

Start at the finish line

When scaffolding lessons, start by considering what the final writing product should look like.

For instance, students might be learning how to write an informational or discursive essay for an end-of-year exam or a literary analysis essay on a novel study. Once the final objective is set, the teacher works backward at a slower pace until the students master the needed skills. The goal is for students to understand the structure and purpose of each component in the writing process.

Help students visualize what the final product should look like by first providing them an opportunity to understand the rubric associated with the assignment to better incorporate those skills in their own writing.

Rubric provides writing expectations

A rubric is an evaluation or grading tool that provides clear, consistent learning expectations, which can differ from assignment to assignment or from one teacher to another. Rubrics can be teacher created or already made available.

One technique I use in my 9th grade Advanced International Certificate of Education (AICE) English General Paper classroom is having my students annotate the end-of course exam writing rubric and define terms in their own words. AICE is a department of Cambridge University and provides examinations and courses that prepare students for life, helping them develop an informed curiosity and a lasting passion for learning.

To make rubric annotations more engaging, students can work in pairs or small groups or even create fun illustrations to demonstrate understanding. The bigger objective of this first step is to show students which areas to really focus on when they begin writing.

Students sometimes spend way more time and energy than necessary writing their opening hook or trying to find the perfect transition words, neither of which may be assessed on the rubric. Understanding the rubic enables the students to focus their efforts on what will be evaluated.

A rubric is like a playbook in sports. A football player vying for the starting quarterback job will study the playbook and present those skills to his coach for evaluation. The student is the quarterback of the essay, ensuring the reader or grader can easily identify all the required elements.

Analyze writing samples with rubric

Next, test the students’ understanding of the rubric by providing samples of finished writing for them to evaluate and score. This is a great chance for the students to color-code and label parts of a sample essay to identify the necessary rubric components, while also making commentary on the writing’s strengths and weaknesses.

Students typically are quick to find errors in other people’s writings, which can lead to them being better self-assessors of their own work, something we will discuss later. In addition, analyzing weak, average, and strong writing samples can provide models for students to use when writing their own drafts, which is especially helpful for struggling writers.

Strategy: I do, we do, you do

Before students can play with their new knowledge, they must receive a certain level of direct instruction to understand the basic principles and foundations of the component being taught. In this next section, I will focus on a scaffolding process I use to teach students how to write an introduction paragraph for a discursive essay. This lesson will take approximately four class periods depending on the length of each class. My school uses block scheduling, which means I see each class every other day for 90 minutes a class period.

‘I do’ – the teacher

Day 1 — Utilize a multi-media presentation to introduce students to the basic components you want them to learn. This might include an attention-grabbing opening, background context on the topic, and a strong thesis statement. During this first step, the teacher can model how to brainstorm these ideas and provide samples of strong and weak introductions. Provide time for students to ask questions and even independently write a few sentences of their own to a given topic. Remind students this is a risk-free trial period for practice. This is also a great time to have students go back to the full sample essays in their arsenal to evaluate those introductions in comparison to the notes they just received.

‘We do’ – the students working in groups

Day 2 — It’s time to allow students to continue practicing, but this time they will help each other in a friendly competition activity. Allow students to work in small groups. I prefer staying within a 3-4 student per group range.

Effective student grouping will take practice, patience, and time. Always set classroom norms when allowing students to work in groups and monitor each group thoroughly. Personally, I’ve found allowing students to select their own group members ensures more ‘buy in’ and a consistent amount of effort from each student. Don’t be afraid of constructive chaos and noise during this part of the lesson. Students will be engaged in conversations about the work, might stand or work on the floor, or move around as necessary per the classroom norms.

Once students are grouped, provide each group with a different writing topic, a large, white self-stick flip chart paper, and a colored marker. The goal is for each group to work collaboratively discussing the material they learned, and then writing a rough draft of an introduction paragraph for their given topic.

While students work, the teacher should circulate around the room and answer any questions. Monitoring students in groups allows the teacher to move from group-to-group listening to the thought process of all students, rather than trying to find time to meet with each student individually.

This is also the perfect scenario to answer questions and address any issues on the spot with the entire class, while also assisting groups who might be off track. Once satisfied with the rough draft, students write a final draft on their chart paper. Have students write their names on the back of the paper to keep work anonymous for the next step.

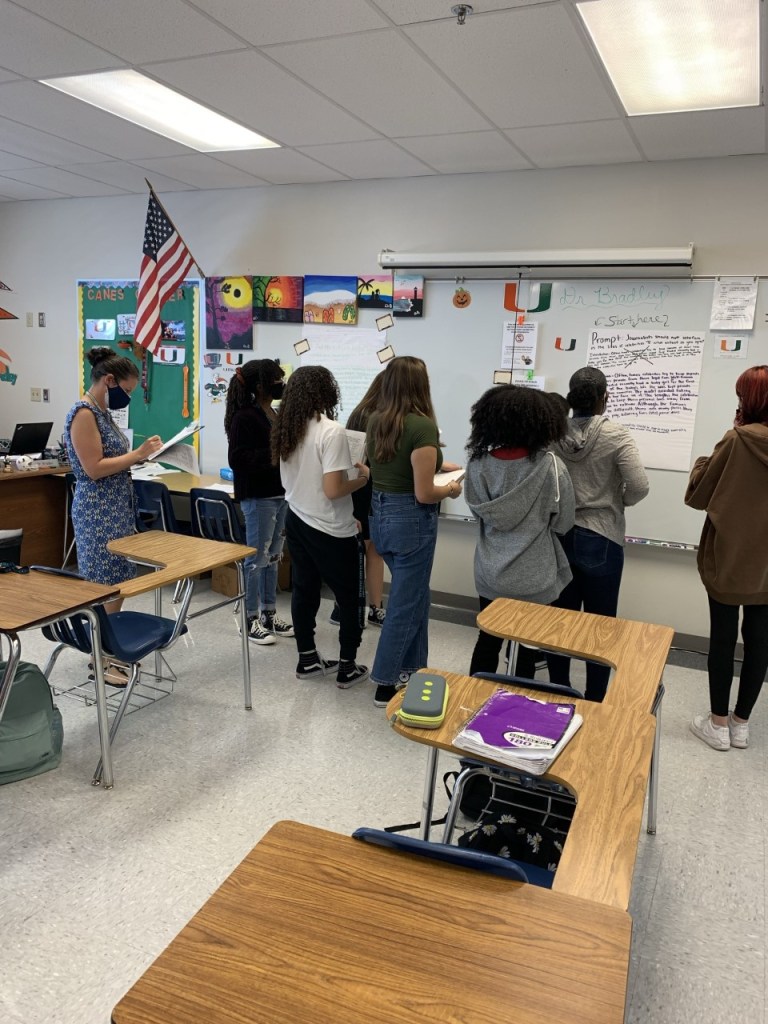

Day 3 — Once all paragraphs are complete, place all chart paper around the room and create a museum of introductions around the classroom. Students will then complete a Gallery Walk Evaluation. Create an evaluation worksheet that includes an area for students to write each poster’s essay topic, and then a simple rubric where students can evaluate and score each required component of the introduction. This is where the original rubric the students previously annotated is useful. Simply pop those rubric requirements into the gallery evaluation worksheet.

After students have quietly and independently scored all introductions, moderate a class discussion poster-by-poster and allow the class to provide feedback on each introduction paragraph. It’s amazing how freely the students will find strengths and weaknesses of each one, while not criticizing any one student directly, and referring to their evaluation sheet (rubric) for evidence to back up their thoughts.

This activity can also be used as a classroom grade. As the teacher, participate in the evaluation gallery walk and score each essay along side the students. By the end of each class period, the teacher has a possible group grade, plus a good idea of any reteaching needed.

‘You do’ – the students working independently

Day 4 — When it is apparent the class has a good grasp of the material, provide an opportunity for students to write their own introduction paragraphs. Allow them to utilize all the resources they’ve acquired up to this point. Before doing all the heavy grading yourself, require the students to self-assess and color code their own work and then peer evaluate another student’s work. After both steps are completed, collect and grade the best and final draft.

Revisions and reteaching

Just because a writing assignment, whether a whole essay or just one component, is graded doesn’t mean the students are finished learning or honing their skills. The final step in the scaffolding process is to allow students the opportunity to revise their work based on teacher feedback.

In my classroom this phase is referred to as points back. I allow my students to revise and rewrite their work, with the quality and quantity of their changes determining how many points back they receive. The points are added back to the original writing grade. Not only does this allow meaningful extra credit points for the students over the course of the semester or school year, but it encourages the students to keep writing!

The more students practice, the stronger their writing skills and the less time grading and providing the same feedback over and over. Scaffolding requires a slower process to begin teaching new skills, but it is worth the time. Once skills are learned and mastered, students have the confidence and knowledge to work at a faster pace.

The benefits of scaffolding

Every teacher wants their students to learn critical skills, but the art of teaching complex lessons can be a daunting task. Scaffolding lessons, especially in critical areas such as writing, will develop independent, motivated, and confident learners. Communication is key throughout all stages of the lesson to set clear expectations. Ensure students are cognizant of the final product and how each step along the way connects back to the learning goal and previously learned skills. In addition, encourage communication amongst students as they work to help their peers in a supportive environment.

Having worked through scaffold lessons, students will leave your classroom with more in-depth writing skills, will learn how to build collaborative relationships with peers, and will feel more empowered when trying something new.

In the end, the classroom teacher will spend valuable, and sometimes limited, time grading more competent work and reaching more students. Last year I taught 185 students and would not have enough time to thoughtfully grade and teach multiple full essays. By scaffolding lessons and allowing my students to independently participate in their own learning process, critical skills were not only explored, but students thrived.

Spending more time initially mapping out smaller chunks of content will lead to more meaningful teaching and learning experiences in the classroom.

Additional Resource: How Scaffolding Works: A Playbook for Supporting and Releasing Responsibility to Students (2023) by Nancy Frey, Douglas Fisher and John Taylor Alarode

______________________________________________________________________________

Dr. Danielle Bradley is a Cambridge English teacher educating 9th grade students at Coral Glades High School in Coral Springs, Florida. During her 22 years teaching in Broward County Schools, the sixth- largest school district in the United States, Danielle has served as an English and journalism teacher, as well as yearbook advisor. She strives to provide her students with opportunities to not only gain necessary skills but to find their passions and believes inspiration begins by allowing students to actively participate in the learning process. In 2023, Danielle was not only recognized as Teacher of the Year at Coral Glades but she was a top-five finalist for Broward County Teacher of the Year. Danielle holds a Master of Arts in Mass Communication from the University of Florida and a Doctor of Education from Nova Southeastern University.